Living Abroad: Experiencing Culture Shock

“When you arrive in a city, you see streets in perspective. A series of buildings without meaning. Everything is unknown, blank. Later on, you will have walked along these streets, you will have been to the end of the perspectives, you will have known these buildings, you will have lived stories with people. When you will have lived in this city, you will have taken this street ten, twenty, a thousand times. At the end of the day, it belongs to you because you have lived there.”

L’Auberge espagnole (Pot Luck / The Spanish Apartment), Xavier.

The art of being a foreigner abroad and in your own country

Since I have been living in Malta, I have faced some unusual situations, which are common to those living abroad. Situations that made me feel like a foreigner. Like a culture shock. I felt like a foreigner in this foreign country. Logical you might say. But, more surprisingly, I also felt like a foreigner when I returned to my own country. A sort of reverse culture shock.

When you live abroad, it is indeed sometimes difficult to know where to call home. Living abroad means belonging to two different places: our home country and our adopted country. In some cases, this can lead to deep questions about our identity, although this is not the case in most situations where emigration is chosen and not forced. Most people who live abroad but are free to return to their country of origin experience certain situations, often funny, sometimes embarrassing.

I will explain why and, above all, tell you about some of the situations I have experienced myself as an immigrant – or expatriate[1].

The art of being a foreigner abroad

Living abroad automatically makes you a foreigner. In our new country, everything has to be discovered. It’s a bit like going back to childhood.

From wonder to culture shock

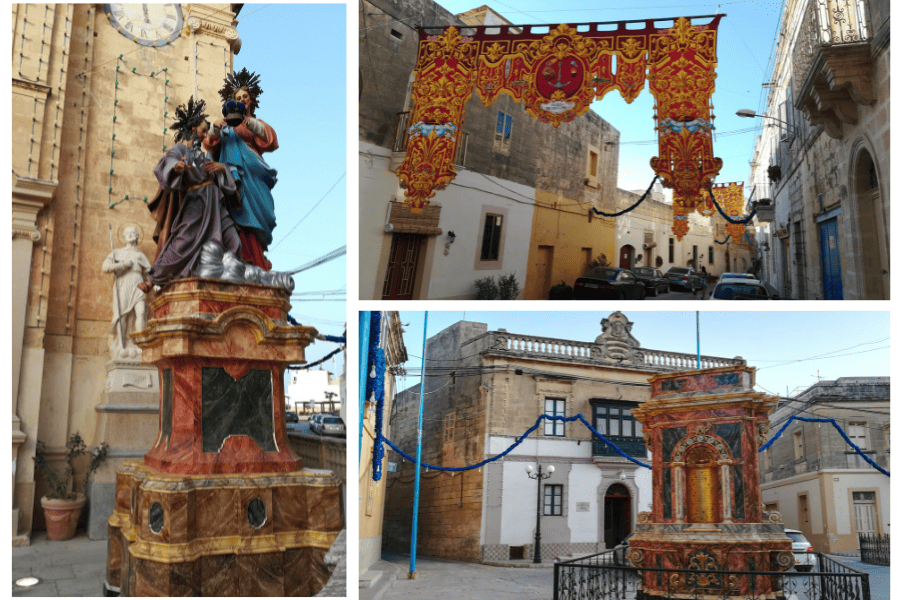

Immigrating or expatriating is, first of all, marvelling at new landscapes, culture and local traditions.

Then discovering, little by little, how the country works. We are not tourists, but immigrants – or expatriates. For the former, their stay in this unknown country will have been an enchanted interlude in their daily life. They marvel and then return to their country of origin, resuming their daily life. For the immigrant – or expatriate – it is a matter of building a new daily life. Immigration – or expatriation – forces us to leave our comfort zone. Every step taken in this new country, every daily concern becomes a learning experience: finding accommodation, shopping, looking for work, enrolling in school or university, making new friends, etc.

The notion of culture shock sheds light on this phenomenon. It refers to the disorientation felt by a person following a change in lifestyle or a move abroad.

Culture shock is divided into several stages:

- the “honeymoon”, during which we marvel at everything,

- the shock itself, where the gap between our culture and that of the adopted country can generate stress, anxiety, a feeling of alienation and isolation, and even the famous homesickness

- adjustment, where, little by little, we integrate into our new environment

- adaptation, when we finally feel at ease in our new country.

I personally find these four stages a bit too schematic. It is certainly interesting and reassuring to put feelings into words, to the panoply of complex emotions felt when we have to adapt to a new cultural environment. But the psychic reality is much more complex. Not everyone will go through these four phases, nor necessarily in the order described above. Finally, some people will never feel completely at home in their new country and will eventually want to leave.

Being surprised

There are many things that can surprise us when we move to a new country. Things that are sometimes insignificant. Things that seem normal to the locals. I experienced this in Malta.

Here, during traditional holidays and feasts, the Maltese have a habit of firing fireworks in the middle of the day, from eight in the morning. Did you think that a public holiday was an opportunity to sleep late? No way! A resounding “boom” will wake you up. Others will follow, preventing you from going back to sleep.

But why are they firing fireworks in the middle of the day, you may ask? Well, fireworks are part of Maltese tradition. They are fired on festive days: the Maltese Festa. During the day, what is important to the Maltese is the noise rather than the colours produced. For me, as a French person (but this is also true in other countries), fireworks are a night-time spectacle, a continuous explosion of colours lasting about 20 minutes. In contrast, in Malta, fireworks are spread out over the day, with many interruptions.

Learning the local language

When we arrive abroad, like children, we have to learn to speak again. Not having the same mother tongue as the locals undoubtedly makes us feel like foreigners. This is especially true when we go abroad to learn or improve a foreign language. In other cases, we already have a good command of the language in question, but our accent betrays our origins. This can be a barrier for some people, who will not dare to speak for fear of being judged on their language level and accent.

However, as I explained in a blog post about language learning, you have to get over your perfectionism and practice. Locals are generally open-minded and will appreciate your efforts to communicate with them. They will welcome you. You will integrate yourself. Gradually, you will feel at home, not like a foreigner.

However, unfortunately, we do not live in a perfect world. In some cases, the immigrant will not be welcomed but excluded, marginalised, and sometimes even victim of discrimination and/or racism.

In any case, it is normal to feel like a foreigner when living abroad.

The art of being a foreigner in your own country

It may seem much stranger, however, to feel like a foreigner back in your own country.

Reverse culture shock

Coming back to your home country after living abroad is not as easy as you might think. Does this surprise you? This phenomenon has a name: reverse culture shock. It is much less well known than culture shock. The person who experiences it often faces the incomprehension of his or her relatives in the country of origin.

Like the phenomenon of culture shock, reverse culture shock does not usually occur when the person travels on holiday, but when he or she moves to a new country (or, in the case of reverse culture shock, his or her country of origin).

This phenomenon is even more difficult to experience because it is unexpected, even for the person experiencing it. Indeed, we can reasonably expect to feel disoriented when we expatriate or migrate, because of the new things we are confronted with. On the other hand, when we return to our country of origin, we think we are “coming home”. This is the problem: what is “home” after all? Before we left, the answer was easy: our home country. But now the answer is much more complex: we feel at home everywhere but nowhere completely.

Because the experience of living abroad has changed us. As we have seen before, we have gradually adapted to our new cultural environment. We have, consciously or not, taken elements of the culture of our adopted country. Sometimes we have left elements of our own culture behind. Perhaps we have changed our views on certain social issues. For example, in France, it is normal to eat foie gras, whereas in other countries it is considered disgusting and cruel.

So when we return to our original cultural environment, we suddenly feel like foreigners. Especially since we were not prepared for it at all. In practice, expatriation – or migration – often involves more preparation and effort to adapt to our new cultural environment than returning home.

Proust Madeleines

In a more unusual way, coming back to our home country is, once again, coming back to childhood. We find ourselves marvelling at things, sometimes insignificant, that our compatriots no longer even notice. It starts the moment we set foot in our own country. We behave like foreigners. We rediscover everything as if it was new, from the landscape to the local cuisine and the customs.

For example, a person who has moved to an arid country is surprised when he or she rediscovers his or her green country.

That person is me.

Malta has a semi-arid Mediterranean climate. From May to September, it hardly ever rains. There are no rivers or lakes on the archipelago. When the rain stops, the greenery disappears. Only cactus and rare trees remain, composing desert landscapes with the rock. So imagine my astonishment when, in the middle of summer, I come back to the West of France for the holidays. The astonishment begins with the landscape that passes by through the window of the plane: the countryside, forests and fields, spread out like an ocean of greenery below. This is when I started to take very strange pictures for my family back in France: pictures of lawns, trees and plants of all kinds encountered on the way. Walking in the forest, smelling the vegetation and the humus has become an exotic experience. I now consider it a privilege. The ordinary has become extraordinary.

Shopping at the supermarket has also become an adventure in itself, full of discoveries. I have rediscovered products that remind me of my childhood. The famous Proust Madeleines.

Lost in translation

Migrating – or expatriating – also means, as I mentioned above, learning foreign languages. So, when we come back to our home country, we can get lost between the different languages spoken. During our experience abroad, we used to speak a different language from our mother tongue (unless we went to a country where our language is spoken). Every day we were immersed in the language (or languages) of our adopted country. We had to live, work, study, shop, meet people, etc. in our target language.

This is what happened to me with English (as a reminder, Malta has two official languages: Maltese and English). I was able to perfect my English until I become fluent. There came a time when I even started to dream in English at night. Fantastic you may say.

But speaking more than one language can lead to funny moments. How many times have I had to say a word in English in the middle of a conversation in French because I couldn’t find it in French? This also happens when we live our professional lives in our target language and do not know the technical terms in our mother tongue. Our compatriots back home may find this funny or strange. How is it possible to forget words in your own language? To mix two languages while speaking? And to no longer find the right words to express ourselves in our mother tongue? In their eyes, we become a bit like foreigners.

Finally, I would like to stress one thing: in this blog post, I am only talking about people who, like me, have chosen to live abroad. I am not talking about the case of people who find themselves forced to leave their country for various reasons (economic, political, climatic, etc.). The “problems” and challenges mentioned above, although real, have nothing to do with the very serious problems encountered in the case of forced migration. People in such a situation have to face the problems mentioned in the first part of my blog post in a more significant way, as well as additional problems specific to their particular situation (e.g. post-traumatic stress after fleeing war).

[1] I prefer to speak of “immigrant” rather than “expatriate”. Both terms, although they both refer to living in a country other than one’s country of origin, are used differently depending on the population they refer to. “Immigrant” is usually used for Africans, Arabs, Asians… non-Westerners, in short, while “expatriate” or “expat” is reserved for Westerners. This difference in usage seems to place the latter on a higher level. I obviously do not agree with this view. I will probably explain the importance of the vocabulary used in a future blog post.

Did you like this blog post? Pin it!